Internet and sexual offenses: beyond common sense

by Digital Rights LAC on September 30, 2014

In this complicated tension between protecting the rights of those condemned and preventing future possible crimes, Internet poses new challenges.

Sebastián Guidi, lawyer*

If you have a Facebook account, it´s a fact that you have stated sometime between the conditions of use, not have been convicted of a sexual offense. If you were convicted of extortion, tax evasion, money laundering, genocide, treason, counterfeiting, torture, theft of livestock or human trafficking, you can continue using your Facebook without problems; but if you were convicted of a sexual offense -which in some countries include the practice of homosexuality, public urination or having consensual sex with a minor, even if you is eighteen years and then get married and have children with that person– your account must be closed.

It is likely that this does not seem unreasonable: maybe there is no group that generates a visceral rejection that sex offenders, any action taken against them can only be criticized as insufficient. They belong to the heterogeneous for George Bataille, the abject to Julia Kristeva. Are totally alien to our logic, we can not talk about them without, civically, shudder. As Hannah Arendt said of radical evil, is so beyond our comprehension that nothing can be said to him but “this should never have happened”.

Maybe that’s why, in more and more countries is easy to found that freedom of sex offenders is restricted even long after completion of their sentences. In 1994, following the death of an eleven years in the state of Minnesota, took part the first law of registration of convicted sex offenders, receiving precisely its name: Jacob Wetterling Act. Since then, the laws governing these records progressively tightened. In many states, sex offenders are settled for life in public records what has led several serial attackers to commit crimes against them-, they are banned in certain occupations -for example, driving funeral cars– and must report periodically the police their residence – which also can not be within a certain distance of schools, churches, clubs, a condition that has led condemned groups to live under a bridge to comply with the law.

Registration policies of sex offenders are, however, based on certain myths that themselves collaborate in perpetuating. For example, they say that sexual offenses have the highest recidivism. However, empirical studies conducted in various countries have shown precisely the opposite: the recidivism rate is lower than that of crimes against life or property. Another fact not widely spread is that cases where sexual offenders randomly choose their victims is statistically a minority. These cases, which are those that appear readily available to memory as the most exhibited by the media hide the vast majority of sex crimes which are committed by people who are into the social circle of the victim: family, boyfriends, husbands, doctors, tutors. Sex crimes tell us more about the hierarchy of genres and the place of sex in our society that the existence of a deviant few, unrecoverable, monstrous beings.These cases, which are those that appear readily available to memory as the most exhibited by the media hide the vast majority of sex crimes are committed by people who are into the social circle of the victim: family, boyfriends, husbands, doctors, tutors. Sex crimes tell us more about the hierarchy of genres and the place of sex in our society that the existence of a deviant few, unrecoverable, monstrous beings.

These reasons may explain the failure of the policy of the records, on which there is a growing consensus among academics. For example, the book by Charles Patrick Ewing, Perverted Justice, includes several empirical studies and, under the suggestive heading “beyond common sense” warns that the only effect of the records, which cost billions of dollars to be made in practice seems to have been to give the impression that the government does something to prevent sex crimes, giving a sense of security to the population and add a new layer to punish those who were convicted .

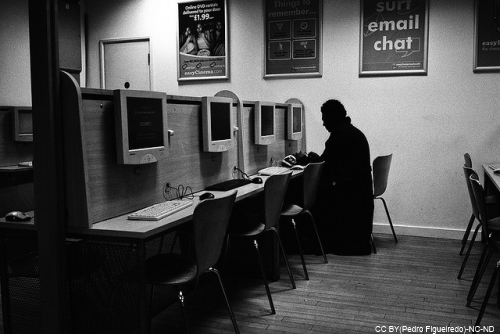

In this complicated tension between protecting the rights of those condemned and preventing future possible crimes, Internet poses new challenges.

In 2012, facing a lawsuit filed by the ACLU, a federal judge declared unconstitutional a Louisiana state law that prohibited convicted sex offenders to access social networks, arguing that the vagueness of the language with which read prevented almost any internet access and therefore violated freedom of expression. After a violent reaction, the state legislature immediately passed a new law that, while not restricting them internet access, they are obliged to declare their status as convicted in any social network in which they participate. A similar law was declared unconstitutional in the state of Indiana.

I do not have anything close to an answer to these problems. I just want to emphasize that, as with the policies of the registry, the data may be a better guide than common sense. As W.S. Maugham said, common sense is made of the prejudices of childhood, the idiosyncrasies of individual character and the opinion of the newspapers. Sexual violence is unacceptable, but resign to take seriously the possibility that those who have committed a crime can be rehabilitated so is. Ignoring the problem only makes it worse. Studies have shown that the rate of recidivism among sex offenders has dropped when they receive appropriate treatment and are reintegrated into society in which they live.

Patty Wetterling, mother of Jacob and one of the main propulsion of registration laws in the 1990s, has recently stated that “they are human beings who have made a mistake. If we succeed, we will need to build a place to integrate them into our culture. Today, one can not enter a church or meeting and say ‘I was a sex offender but I went through treatment, now I have a lovely family and I’m grateful to belong to this community”. Surely soon, in our countries, we have to wonder if there is room on the internet for success stories. Maybe we need to start thinking about the answer.

:::

*Sebastián Guidi. Lawyer. Assistant Professor of Constitutional Law. @sebasguidi