The use of drones in Chile and DAN 151: Innovation regulations are necessary, but insufficient

by Digital Rights LAC on May 7, 2015

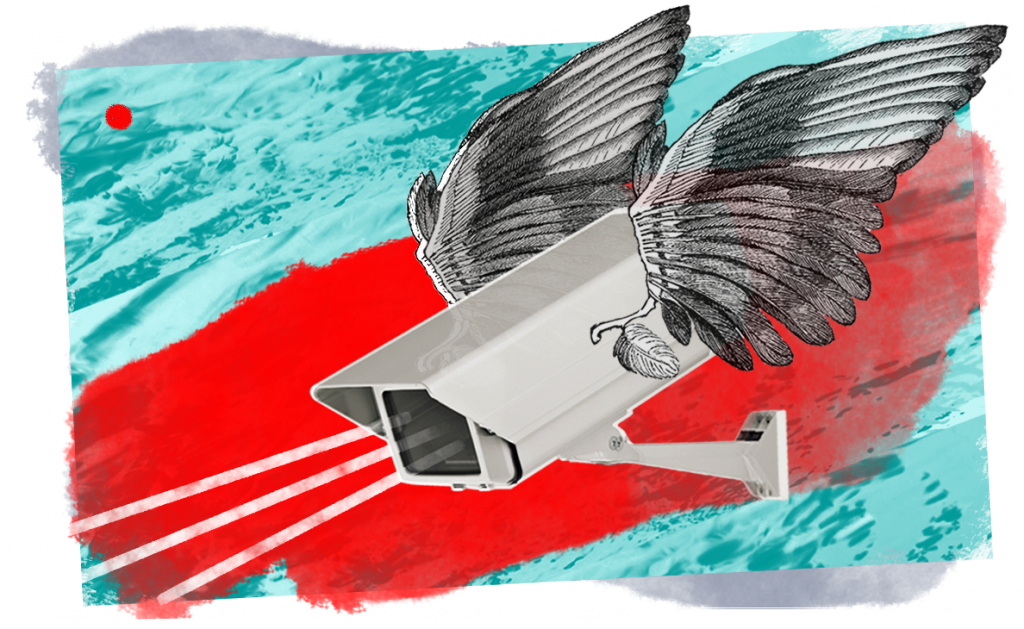

The use of drones is becoming more widespread, they are available to those who can buy them and are becoming a common sight at football matches, concerts and other events and mass gatherings of people. Depending on how they are used, these devices may violate some of our rights, regarding our lives, property and privacy. In Chile their use has just been regulated, but are these norms enough?

By Valentina Hernández, Derechos Digitales

The International Civil Aviation Organization (OACI) recently estimated that by 2018 there could be an international law regulating the use of drones or unmanned aircraft. As this kind of technology is on the rise and poses a number of risks, The Directorate General of Civil Aviation of Chile (DGAC) wisely decided that it was necessary to draw up its own rules as soon as possible. Thus, on April 2nd, 2015, the first law was presented, the aeronautics regulation (DAN) 151.

As we said before, the use of remotely piloted aircraft could lead to serious damage of the fundamental rights of the population, especially those related to life, property and privacy. For the authorities, the most palpable threat is more linked to physical integrity and properties: some of these crafts can weigh several kilos and fly at high altitudes, so if they fall or crash, they could easily cause serious damage or even death.

However, there is another big risk. Since these devices can take pictures and videos of our more intimate spaces from the air, it is not hard to picture how their use could easily become invasive, especially with the difficulties of pursuing any legal responsibilities.

Regarding the protection of our rights to life, physical integrity and property, we have a series of measures within DAN 151 that are intended for our protection, such as the flexibility of the propellers, the existence of an emergency parachute, compulsory insurance payments and an affidavit of responsibility, among other things. Similarly, a list of restrictions listed for using a “drone”, including the general prohibition of putting people’s lives at risk.

Furthermore, other requirements are considered, such as needing special permission to handle heavy drones, the registration of the craft, being certified after receiving theoretical and practical instruction, and having to pass an exam.

In contrast, the regulation regarding the right to privacy is very meager. We were only able to find a general prohibition, stipulating “to not violate the rights of people in their intimacy and privacy,” without establishing any specific measures.

Excluding the most obvious cases of transgression (photos and videos), carried out by individuals, there are much more complex aspects to take into account, such as state surveillance through the use of drones.

For the last two years, the Chilean government has been buying drones for law enforcement and surveillance, without being transparent to the public or about the acquisition and use of these devices. This aspect of the problem is not addressed in DAN 151, despite its importance.

Drones can be used to record small details that, viewed without context, might seem irrelevant; for example a photo of a person walking down a street. But analyzing photograph details such as the time, the street, the direction in which the person walked and adding data from other similar images, make it possible to predict possible behaviors and habits to discover more about our general behavior. This type of threat must also must also be dealt with by a new legislation regulating the use of technologies that can be used for invasive purposes.

With just a small squad of drones you can monitor entire regions. The technical specifications available on the more advanced models include several types of cameras along with laser, thermal and ultrasound sensors, plus other technologies which could gather as much information. This would not only make the right to privacy illusory, but other matters as well, such as the right to due process. The potential threat to the rights of life, privacy and property, posed by the government use of drones is much higher than that of the private sector. The picture is even far more complex if we consider that for the moment we have no way of identifying the state use of drones.

The use of drones is not a particularly bad thing in itself. Like with any form of technology, they can have a number of legitimate uses, and there are those who perform legal economic activities through the use of these crafts. But given their potential risk, there is definitely a need for minimum conditions, governing their use.

The problem exists when the use of technologies infringe the fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals. That is why we expect a definitive law that can guarantee and protect them.

Translated by Frank Roach.