The Blind Treaty and the “Miracle of Marrakesh”

by Digital Rights LAC on July 17, 2013

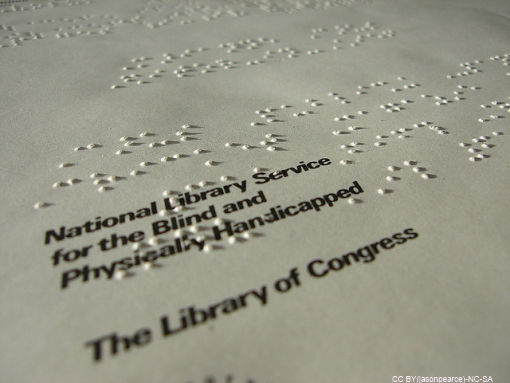

After years of negotiations, the diplomatic process for the approval of the Treaty which provides exceptions and limitations to copyright for visually impaired people came to an end. The Treaty of Marrakech is a strong illustration of the links between copyrights and human rights, embodied in an international legal instrument that tries to balance intellectual property and access to culture, information and knowledge.

By Pedro Belchior and Eduardo Magrani, Centro de Tecnología y Sociedad.

After a long diplomatic process, it was possible to reach an efficient Treaty which provides exceptions and limitations to copyright for the benefit of the visually impaired.

The Diplomatic Conference of the World Intellectual Property Organization – held in Marrakech in the last two weeks of June – was an example of important negotiations and of the possibility of defeating the power exercised by the United States and the European Union.

After a classic battle between the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere, the results of the Treaty will benefit more than 314 million people with significant visual impairment in the world, according to the World Health Organization, since only 5% of all books published annually in the world are available in accessible formats for people with visual impairments.

In fact, as it was expected, it was not possible to approve a complete treaty. But ultimately, such a treaty would never be possible in a diplomatic process fairly open, as we witnessed.

Still, the interests of representatives of the copyright industry – captained by organizations such as the Motion Picture Association – were mitigated on behalf of the visually impaired. Anyway, the attempt to defend the current business model based on holding exclusive copyright and trading their ownership works with all those who intend to make any use of them did not prevail.

The great fear appointed by the corporations’ representatives was the mere possibility that the Treaty would represent a first step towards changing the copyright system that was supporting their current business operations. In fact, that’s what is happening after its adoption and it’s one of its major goals.

The industry’s interests were rigidly upheld by the European Union and the United States, which over the negotiations adopted largely inflexible positions substantiated even by the irrational fear of misappropriation of the adapted works by people who don’t possess visual impairments.

On the other side of the conflict, we have the visually impaired, who can’t adapt works to make them accessible because most of the national copyright laws expressly prohibits it. Institutions such as the World Organization of the Blind and the regional organizations of the blind, which fought for this treaty since 2004 in WIPO, were supported by most of the countries of the Southern Hemisphere.

Undoubtedly, the main interest of the visually impaired was to create an express exception to copyright in order to transform textual works without the necessity of applying for authorization or affording exorbitant amounts of money. Thereby, they would have easy and complete access to those works, equaling to other citizens.

The countries of Latin America have had a major contribution to this conquest. They contributed directly to the approval not only of a treaty, but of a good, practically effective one. Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico and Paraguay, among others, have had a rigid and faultless performance in front of pressure from the United States and the European Union. The public stance of the former was largely settled and intense, aligned with the interests of civil society and the visually impaired. Also, Peru had been designated as a facilitator in a critical moment of the negotiations and was also crowned as one of the great heroes of the Treaty for the visually impaired.

The Treaty was seen by the blind and civil society groups as “The Miracle of Marrakesh” and really brought us reasons to celebrate.

Initially, it is a treaty approved by WIPO that covers and recognizes, apart from common commercial aspects of intellectual property, some basic human rights, such as access to information, culture and knowledge.

The Treaty is also historical, since it has been considered the first international instrument drafted by WIPO that provides exceptions and limitations to copyrights, which in itself is already a victory.

Likewise, the construction of this Treaty is part of the strategy constructed in order to allow the design and approval, at first, of a treaty which creates copyright exceptions for the visually impaired, setting the stage for further discussions. Therefore, in the wake of these recent advances, it is intended now to prepare another treaty that creates exceptions for libraries and archives, and later a third treaty which creates exceptions for educational purposes.

And, after all, the rights of the visually impaired have been recognized and are now expressly provided in another international instrument. One cannot say that this was the ultimate measure to end inequalities perceived internationally and especially in developing countries, but it certainly was an essential step for the significant reduction of disparities.

Still, we must criticize the fact that many agreements and negotiations were conducted behind closed doors, forbidding civil society to follow thoroughly all the discussions and positions. This may have allowed some impairment eventually manageable at the time.

Finally, after years of discussions in Geneva, plus two weeks of intense conversations and daily contact with negotiators, delegates, ministers, members of civil society, academics, and especially visually impaired, victory seems extremely deserved.

Unique people dedicated all their efforts to achieve the best possible text and only someone completely oblivious to the debate would be able to say that the Treaty could be substantially better. It was a historic victory, which should be honored with the immediate ratification by countries until they hit the 20 ratifications required for the Treaty to enter into force. Also, the continuation of a positive agenda in WIPO discussions should be kept on the agenda.

Finally, on a cold and simple analysis, it was an apparent opposition between the two kinds of rights: the rights of private copyright holders – most of whom are not even the authors of the works – to prevent works under their control to be used in any form without a payment, and the human rights of the visually impaired to have access to information, culture, knowledge and education so that they can sustain themselves as worthy people. After all, which one should prevail?

Eduardo Magrani y Pedro Belchior, investigadores del Centro de Tecnología y Sociedad (CTS)

E-mail: eduardomagrani (at) gmail.com; pedrobelchiorcosta (at) gmail.com