Computer crime: the necessary human rights perspective

by Digital Rights LAC on November 22, 2013

By Paz Pena Ochoa

In a context of increased criminalization of cybercrime, it is time to reflect on how our laws respond harmoniously with respect for the human rights of citizens. The conclusions drawn may prove to be more than worrying.

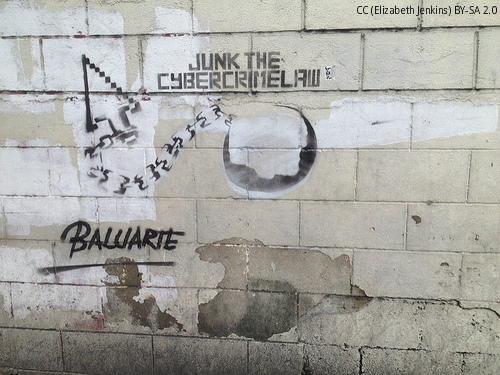

Spam, fraud, child pornography and virtual terrorism, among so many other things. With the development of Internet, computer crimes have become more frequent, sophisticated and, therefore, more important in the public opinion. This has led to several laws around the region being concerned with persecution, even though in many cases they end up damaging other fundamental rights of the rest of the citizens.

The seminar “Computer Crime: New Critical Perspectives“, a joint initiative of the Center for Studies in Information Law (CEDI) of the University of Chile and Derechos Digitales NGO, sought precisely to take a look from this perspective. At the various panel discussions, the conclusions were more than disturbing.

This, for example, is the case of law 19,223 for Chilean cybercrime, which has been in force since 1993, and that several panelists criticized for its lack of clarity regarding penal types, its vagueness in defining computer rights and ambiguity when distinguishing protected rights, even claiming that the law should be repealed like in the case of Renato Jijena, of the Catholic University of Valparaiso.

For Juan Carlos Lara, director of contents at Derechos Digitales NGO, all these weaknesses of the law are troubling when the persecution of cybercrime is necessary, proportionate and appropriate. As he emphatically pointed out, harmonic and sensible standards are required that are respectful of human rights and avoid falling into obvious civil rights abuses such as today’s Peruvian cybercrime law.

However, the discussion went further and also touched upon the controversial topic of intellectual property crimes. In this case, the figures are revealing. In Chile, on average there have been two thousand people convicted of piracy in recent years, whereas in the United States, home of the Hollywood film industry which exports high standards of intellectual property protection to the whole world, there have been 20 times fewer, somewhere around fifty convictions a year.

This apparent imbalance and huge criminalization that continues throughout most Latin American countries, masks an even more disturbing reality for Alberto Cerda, the international affairs director of Derechos Digitales, who believes that the criminal law in the region is used disproportionately under the guise of protecting intellectual property.

According to Cerda, and consistent with other authors such as Joe Karaganis, the underlying problem of piracy is not a criminal matter, but rather a clear market failure. In other words, in Latin America piracy exists because of a lack of service provision, and if there is any at all, it is deficient. Cerda states that “Up until a year and a half ago, an owner of an iPhone or an iPod had no way of legally accessing music. Now, only iTunes has begun providing services around the region, the same can be extrapolated to the case of movies, where Netflix has only recently arrived to this part of the world. “

A similar case occurs with the book industry, because while there may be an availability in the region, they are, however, very expensive and do not consider the disparity of income or levels of development between the countries. Cerda gave the attendees of the seminar an explicit example by pointing out that for an American citizen it costs an hour of work to buy a book, for a Chilean it would cost eight hours and for a Brazilian two days.

But even though there are several evidences point towards a market failure as a cause of piracy, the laws and international treaties (including the Trans-Pacific Partnership, TPP) attempt to find a “solution” through the criminalization of the conduct of citizens, using the criminal code in ways that often threaten human rights.

In this sense, for Cerda the problems in Latin America are shared by most countries: from behaviors that are too broad to be defined yet considered possible offenses against intellectual property; high criminalization (for laws, for example, the urge to make profit is not relevant for the sentence); those accused of such violations having to prove they are not guilty, rather than the police and judges working on the principle of presumption of innocence, and last but not least, the disproportionality of the penalties for these types of crimes (in countries such as Peru and Colombia, punishments are higher for stealing than for copying).

Despite the many criticisms and new perspectives that were discussed at the seminar, a certain level of uncertainty remained among the audience and panelists when recognizing how certain international treaties could continue forcing non-harmonic laws upon human rights.

Without going any further, the imminent entry into force of the TPP in countries like Mexico, Peru and Chile was discussed, which would accentuate all the features of criminalization of intellectual property crimes that were criticized at this meeting, but with an added negative twist: that national Congresses will have limited means of intervention and will have to apply the agreements through legislation that will end up being harmful to human rights in this regard.

Paz Peña is director of communications for Derechos Digitales NGO

paz@derechosdigitales.org

Translated by Franklin Roach