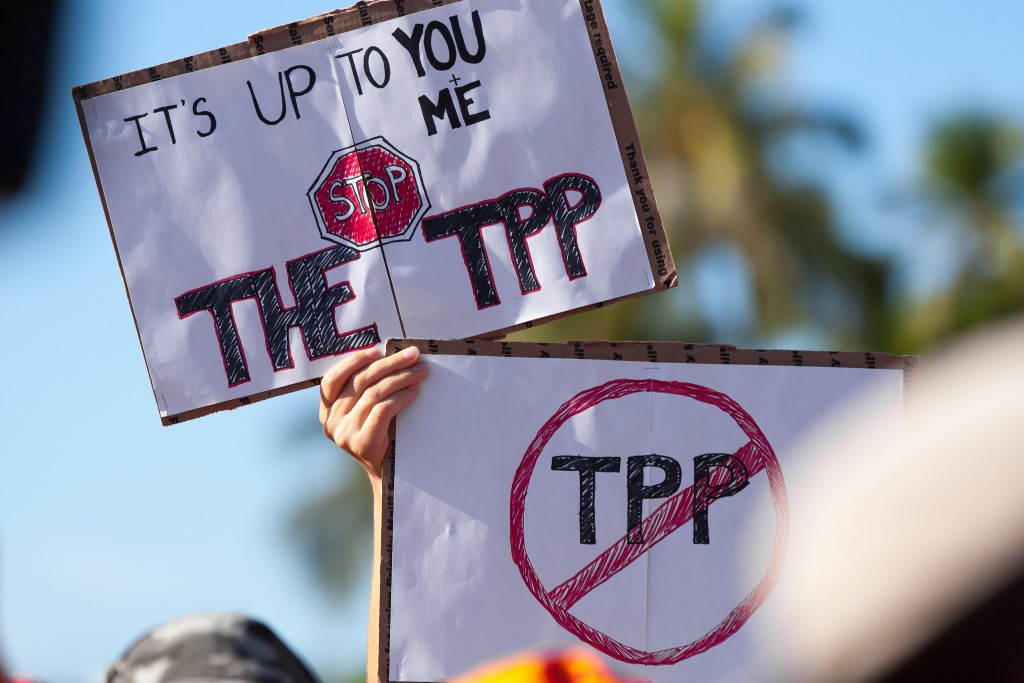

The last big battle of the TPP

by Digital Rights LAC on September 23, 2015

The advancements achieved in the negotiation of the agreement are increasingly bigger, the maneuvers of the civil society are made more and more difficult and, even though better perspectives regarding technological matters can be seen, there is a big obstacle to overcome in order to assure the sovereignty of the countries: the Certification.

By Pablo Violler, Derechos Digitales

The results of the last round of negotiations surrounding the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that took place in Hawaii were interpreted as a failure by the countries that expected to sign the pact in Maui. This free trade agreement that 12 Pacific Rim countries, including Mexico, Peru and Chile, are secretly negotiating has already experienced delays in the past. This time the last attempt to sign the agreement was surprisingly frustrated by a controversy between the USA, Japan, Canada and Mexico, regarding the rule of origin in the automobile industry and, to a lesser extent, the dissatisfaction New Zealand has regarding to the export quotas in the dairy industry.

Nevertheless, the chapter about pharmaceutical patents—and particularly the protection of biological drugs test data — is a stumbling block to reaching an agreement. Let us remember that Chile’s Minister of Foreign Affairs said the country would defend its position of not extending the term of protection of biological drugs test data to the very end.

This, however, does not mean that there was no progress in the round of negotiations. On the contrary, it is estimated that there is a 90% consensus on the treaty and that 27 out of 30 chapters are already closed.

The advanced state of progress reached on the negotiation and the level of consolidation on the text make it difficult for the civil society to have a significant effect on the final TTP text. On the other hand, although there have been advancements in subjects such as the automatic taking down of contents, technological protection measures and intermediary liabilities, all of this progress has been achieved in the form of exceptions and flexibilities in the language of the text.

This exceptions and flexibilities in the language would theoretically allow the countries to implement a more balanced legislation appropriate to their local circumstances. However, even this possibility is uncertain, as the countries have not yet defined a mechanism for the entry into force of the agreement.

In that regard, the United States’ original proposal was to export an equivalent of its certification system, in which an entity that is external to the negotiation determines if the legislation implemented by a country meets or does not meet the agreement’s requirements; this, in practical terms, involves imposing a given interpretation of the content of the obligations. Consequently, an important percentage of the negotiating countries were against this proposal as it constitutes an intrusive and unilateral process. Comparing the implementation experience between the Chile-USA Free Trade Agreements (TLC) and the Peru-USA TLC serves as an illustrative example.

In effect, if the developing countries have invested their energy and efforts to oppose the maximalism of the developed countries within TTP negotiation arena, it has been done in order to reach exceptions and flexibilities in the text and to be able to use them at the moment of implementing their legislation. The United States’ Certification proposal turns this possibility into an illusion.

In order to bypass this potential impediment, Japan has proposed an alternative system, in which the member nations are given a period of two years to formally approve the treaty as per their internal legislation. The incorporation of countries which have not confirmed the TTP after two years would be reviewed by the free trade committee that is part of the same agreement, which is made up of countries that are already members.

Although this proposal constitutes an advancement there are still doubts as to how the free trade committee will approve the entry of countries that take more than two years to approve the TTP. If this is done through an intrusive and unilateral process, the mechanism of certification proposed by the USA will simply be delayed by two years.

Additionally, the Japanese proposal requires that, within the first two years a number of countries equivalent to 85% of the GDP that the treaty comprises have approved the TTP in order for this to work. This percentage is impossible to reach without the approval of both Japan and USA. In practical terms these countries are given a disproportionate amount of negotiation power that allows them to apply a “factual certification” over the rest of the negotiating countries so that they implement the treaty in a way that benefits both of their personal interests.

The entry into force mechanism can make a difference between a balanced treaty and one in which the agenda of the developed countries is imposed. Consequently, it is necessary to agree on a system that is respectful towards the sovereignty of each country and the fundamental rights of their citizens. As long as this is not achieved, everything indicates that this will be the last great battle against the TPP.

Image: (CC BY) SumOfUs / Flickr