The low involvement of civil society in the Telecommunications Act in Mexico

by Digital Rights LAC on May 5, 2014

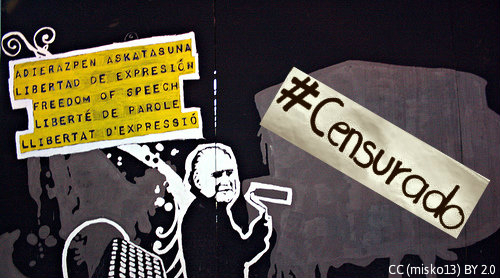

The Telecommunications Act has been controversial not only because it damages freedom of expression on the Internet, but also because throughout the process of its discussion, the contributions of civil society have been minimal. What will happen to public interest in this legislation under these conditions?

By Israel Rosas*

The first year of Enrique Peña Nieto’s term in government and the Federal Executive Power of Mexico was characterized, amongst other things, by the impulse triggered by a series of amendments to the Constitution, known as structural reforms. The financial, educational and telecommunications sectors were the first to be considered, thanks to the Mexico Pact, an agreement between the Office of the President and the three main political forces.

The alliance, in addition to promoting reform proposals, also served to expose the lack of participatory opportunities that exist within Mexican civil society. At present, the pact is no longer in effect. However, the legislative practices have not changed, as was seen in the process of opinion of the new telecommunications legislation.

The Pact for Mexico

A day after Peña was sworn in as Constitutional President, an agreement was announced between the Presidency of the Republic and the three main political parties of the country. The pact included the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the driving force behind Peña Nieto’s candidacy; the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), the main force of the partisan left; and the National Action Party (PAN), the right-wing party that had just handed over the presidency.

Consisting of a total of 95 commitments, grouped into five major agreements, the pact aimed to carry out a radical transformation of the country through legislation. Commitments 39 to 45 exclusively looked at reforms of the telecommunications sector.

Constitutional reform in telecommunications

The initiative for this sector was filed on March 11th, 2013, and sent to Congress as part of the work undertaken by the Mexico Pact. The document was signed by Enrique Peña Nieto and the PRI parliamentary coordinators, the PRD, PAN and the Green Party of Mexico (PVEM) in the House of Representatives.

Once in the Chamber of Deputies, the ruling issued by the commissions was approved by the House with 414 votes in favor (397 provided by the signatory parties of the pact), 50 against and eight abstentions. The reservations put forth by other opposition parties were systematically rejected without even being discussed, so the ruling was referred to the Senate.

In the Senate, the legislative process was similar. The ruling issued through the commissions was approved by 118 votes in favor and three against. 117 votes in favor were provided by the de facto coalition which included the PRI, the PRD, PAN and the PVEM. The reserved items were approved under the terms of the ruling, employing the methodology used in the Chamber of Deputies.

A couple of additional modifications meant that the initiative had to return to both chambers, once more leading to similar results. On April 30th, 2013, the ruling was adopted in the Senate and was referred to the state legislatures of the interior of the Republic, seeking the approval of the majority, which is needed for a constitutional reform.

What about civil society?

After being approved by the majority of state congresses, the minutes were declared constitutionally valid by the Permanent Commission of the Congress of the Union, during one of the breaks. The initiative was referred to the Official Gazette for publication, on June 11th, 2013.

Two of the transitory provisions of the Decree of constitutional reform make it obligatory for Congress to issue a new legal order and make it fit into the existing legal framework under the new text of the Constitution. Although the deadline for making these amendments expired in December 2013, it was not until March 24th, 2014, that the Federal Executive sent the secondary legislation initiative to the Senate. It was at this point when the controversy erupted and several civil society actors warned about the consequences of this law, regarding freedom of expression on the Internet.

The description of the initiative states that it was created by taking into account the more than 33 contributions made from various stakeholders within the sector. It highlights those sent by trade chambers and associations such as the National Association of Telecommunications (ANATEL), the National Chamber of Electronics and Telecommunications Information Technology (CANIETI), the National Industry Chamber of Radio and Television (CIRT) and the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). The document also refers the inquiry to international organizations, but although it notes that some of the contributions were sent by civil society actors, it does not specify the amount or specific nature of the details.

In the Senate , the Joint Committees of Transport and Communications, Legislative Studies, and Radio, Television and Film, who are responsible for creating the ruling of the initiative, formulated a work program to undertake this responsability. The document considered the possibility of conducting public forums to find out the opinion of experts on the issues addressed by the draft legislation.

Unfortunately, the criteria for choosing the speakers were not clear. In addition to this factor, a good portion of the participants were representatives from industry, while civil society was relegated to a secondary role. Even if there were any interested parties who found a way of sending their own contributions, it is not clear what role they could have played in the process of analysis and ruling of the legislators, not even if they had appeared on the Senate’s micro site which was allocated for this purpose.

The composition of both houses of Congress allows the political agreements to prevail over technical discussions, even in matters related to telecommunications and even without the Mexico Pact. This is especially the case when a constitutional amendment requires the vote of two-thirds of the legislators, but the adoption of the new legislation only requires the votes of a simple majority. In this scenario, it matters very little whether the views of society are included or not in the initiative which is in question.

*Israel Rosas is a member of the Mexican Chapter of the Internet Society and Wikimedia

Twitter: @irosasr

Translation: Franklin Roach