What is the future for net neutrality in Brazil?

by Digital Rights LAC on December 21, 2013

By, Ivar A. M. Hartmann

Brazilians waited all 2013 for a new, positive development on the voting of the Marco Civil da Internet at the Brazilian Congress. After Edward Snowden’s leaks and a big story on a nation-wide Brazilian newspaper revealing that even the Brazilian government had been spied on, president Dilma Rousseff decided to place the bill on “Constitutional Urgency”.

This meant that after 45 days congressmen would be forced to either approve or repeal the Marco Civil before they could vote on any other regular bills. Even this effort turned out powerless to push Marco Civil forward – nothing will happen before 2014. The reason is becoming well-known to members of the Latin American and Caribbean internet governance community: net neutrality. With this new legislation approved, Latin America would become a world pioneer on the protection of net neutrality, with two big countries enshrining it in legislation. Sadly, Brazil has so far failed to trail the path of Chile.

There are other dispositions in the bill that have been the object of heated debate. Intermediary liability ensues, according to the Marco Civil, only after a court order to remove content. Even though (or perhaps exactly because) this model better protects free speech, it upsets content providers who were quickly catered to by the Minister of Culture. She asked that a paragraph be added to the intermediary liability provision stating that the court-order-and-takedown model didn’t apply to alleged copyright violations. Still, this didn’t stop the push for the Marco Civil.

Then later this year came the ill-advised idea to force internet companies to host datacenters in Brazil. Despite warnings (from everyone who knows anything about how the internet works) that such an obligation would certainly backfire and should be dropped from the Marco Civil, the government stood ground and insisted on it. This too wasn’t enough to stop the bill on its tracks.

But the pipe owners have got their backs in the Brazilian Congress, as in legislative bodies around the world. And they want anything but being merely the pipe owners. After years of a drafting process that included absolutely every sector of society and with the official and full support of the Executive branch and the ruling Labor Party, the Marco Civil was still no match for the telecommunication industry.

The Brazilian National Telecommunications Agency (ANATEL) and Ministry of Communications are the entities favored by telcos to deal with net neutrality. A year ago, when the Marco Civil was already jammed in Congress, ANATEL signaled it would take on the task of creating and deciding on neutrality rules – a draft regulation of “multimedia communication services” would forbid packet discrimination while also establishing a wide enough exemption to render such prohibition meaningless. The Agency later passed a version of the regulation that contained a simple mention of the telcos duty to respect net neutrality “according to the law”.

The Minister of Communications, Paulo Bernardo, had always been adamant that ANATEL should be the one to decide on net neutrality. Especially when a previous draft of the Marco Civil would have the government consult the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (CGI.br) on neutrality issues. The draft said nothing of CGI.br actually regulating neutrality, but the mere mention was enough to give telcos the creeps: they would rather have a legacy governmental agency easily susceptible to capture (ANATEL) regulate net neutrality than a transparent multistakeholder committee with a record of impartiality.

In the Brazilian Congress, the most vocal protector of the financial interest of telcos has been Representative Eduardo Cunha. According to him, net neutrality would hurt the business model possibilities of telcos and cable companies – they would no longer be able to create plans with different data caps. While it’s clearly false that a ban on treating data packets differently according to their content also entails a ban on treating different amounts of data packets differently, there is some truth to such argument.

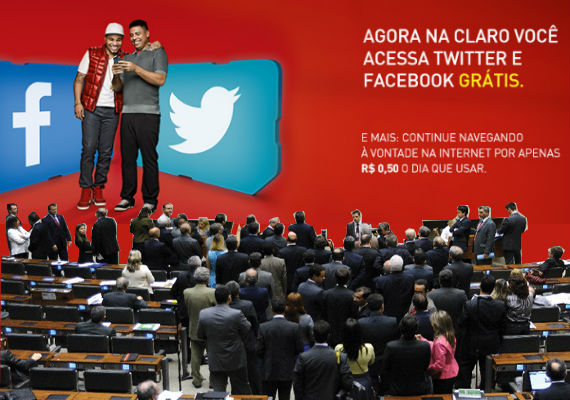

There is in fact a business model that telcos wish to protect against net neutrality. And contrary to what is usually conveyed in these debates it is already a reality. One of the big mobile phone carriers cheerfully advertises the fact that its users can surf Facebook as much as they want without deduction from their data plan. Not Google+ or Diaspora, of course. Those aren’t favored. ANATEL has done nothing to discourage such business practices. Meanwhile, the news from Chile shows that even with a clearly stipulated rule in the law the tendency of telcos to discriminate packets remains strong.

Funding the necessary infrastructure for the future of broadband is by no means a simple issue. But there are several possible business and investment models that are perfectly compatible with net neutrality. In any event, the realization that the pipe owners must necessarily be “dumb” and start being treated like any other common carrier is the result not of an economic rationale, but rather of political and moral considerations which stem from internet access’ fundamental right status.

The latest rumors are that the telcos have finally entered into an agreement with the bill’s rapporteur and net neutrality champion Representative Alessandro Molon. Until the Marco Civil goes into force, however, anything can happen. After Chile, a legislative win for net neutrality in Brazil could spur a tendency of pro-neutrality regulation in all of Latin America and the Caribbean. One thing is for sure: the stakes are extremely high for internet users and telecommunication companies alike.