Internet Rights in Ecuador : the possible triumph of activists?

by Digital Rights LAC on December 21, 2013

The appearance of the “Free Internet” coalition was crucial in raising the alarm on one of the most controversial articles of the new criminal code, that would allow the monitoring of Internet. But is the possible end of Article 474 sufficient enough for the government to respect fundamental rights in communications?

By Analia Lavin and Valeria Betancourt, APC

After the revelations of Edward Snowden in June this year, the Assembly of Ecuador passed a resolution rejecting the “illegal and indiscriminate use of espionage” carried out by the United States, and considered it an attack against the “right to privacy and the privacy of all the inhabitants of the planet”. A few months later, the Ecuadorian representative in his speech at the UN General Assembly, criticized how these practices ignore “the right to privacy and freedom of expression of all citizens .”

During the same period, however, the Assembly of Ecuador discussed and approved a new penal code that legalized the systematic surveillance of communications, jeopardizing the exercise of these rights that it zealously defended in the case of U.S. practices.

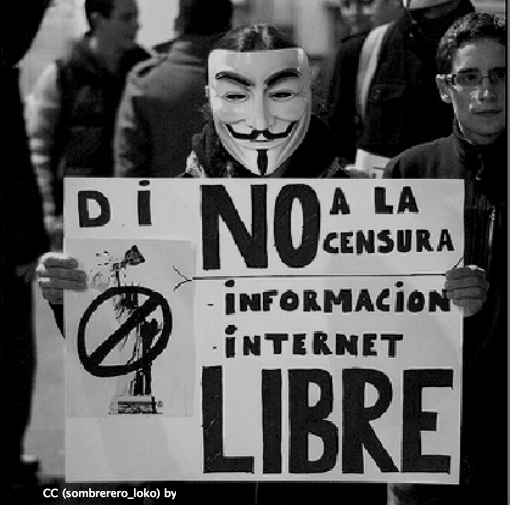

Civil society organizations, user groups and Internet users closely followed the discussions on the law and got access to drafts which put them on alert. Together, they formed the “Free Internet” coalition and launched a campaign that included digital activism, along with meetings with Assembly members from all the political parties and reports sent to the president. Although at the time of writing this note, there is still no official confirmation, it appears that the most problematic aspects will be eliminated from the final text.

Article 474, the most controversial aspect of the new penal code, requires Internet service providers to store user data “in order to carry out the corresponding investigations”. This article, however, goes far beyond mass state surveillance, extending the same storage requirements to “subscribers of telecommunications services that share or distribute their voice or data interconnection to third parties” and seeks to bring these policing functions to the citizens themselves, promoting a culture of permanent distrust where everyone could potentially end up spying on each other.

Besides contradicting rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, this item violates the Constitution of Ecuador, which recognizes the right to personal and family privacy. It also establishes that both privacy and interference of virtual correspondence, require minimum guarantees as authorized by the owner or judicial intervention. The alertness raised by Article 474 would be generalizing the limitations of a law which, on the contrary, should be the exception. As stressed by Ecuador’s representative to the UN General Assembly, and mentioned above, privacy is closely related to freedom of expression, and practices such as censorship affect the quality of democracy in the nation.

But Article 474 not only legitimizes the systematic violation of fundamental rights of citizens, it also presents serious problems in its implementation. Storage of “data integrity” of people’s communications for at least six months that are required by law, would force service providers to exponentially multiply their storage capacity, to update their physical and virtual infrastructure, and strengthen their security protocols.

The very high costs of these measures, which will probably end up being transferred to the end user, will also have an impact on the investment priorities of companies, who would have fewer resources to extend their services to less profitable areas.

Finally, the volume of information and data which the law requires to be preserved (basically all Internet traffic and telecommunications in a country of fifteen million people) multiplies the risks of interception, analysis and non-consented use for commercial or political purposes as well as compromising the security of electronic economic transactions of the governement, among other things. If this article is approved, the criminal code, instead of protecting internet users would actually expose them to conditions of extreme vulnerability. Such legal content, ultimately limits the deployment of network usage for social, economic, political and cultural development.

These were some of the arguments used by the “Free Internet” coalition. Activists involved in the campaign, however, think that the decisive factor was the decision on privacy in the digital era, recently approved by a committee of the UN General Assembly. The resolution, pushed forth by Germany and Brazil, states that the “monitoring and/or interference of illegal or arbitrary telecommunications, as well as the illegal or arbitrary collection of personal data, are highly invasive acts that violate the rights to privacy and freedom of expression and may contradict the principles of a democratic society” Ecuador is among the 23 countries that signed the resolution.

The assemblywoman who announced the annulment of Article 474 on Twitter (an announcement that, again, has not yet been made official), referred to “political and ideological coherence” as the reason behind this decision. While Ecuador supports such resolutions at the UN and offers political asylum to Julian Assange, to position itself as a world leader in human rights, the situation within the country is worrying. This year, for example, an organic law of communications was approved which, among other problematic aspects, demands electronic media to register the identity of those who publish comments. If it seeks political coherence, Ecuador must renew its commitment to the fundamental rights of its own citizens.

Analia Lavin is part of the communications team of APC

E – mail: Analia@apc.org

Valeria Betancourt is Director of the Policy Program of Information and Communication APC

E – mail: valeriab@ apc.org