Those Colorful New (Google) Cars in Argentina

by Digital Rights LAC on November 22, 2013

By Atilio Grimani and Emiliano Villa

Street View’s arrival in Argentina poses different challenges that must be overcome to balance out this tool’s benefits with its potential violations of the right to privacy.

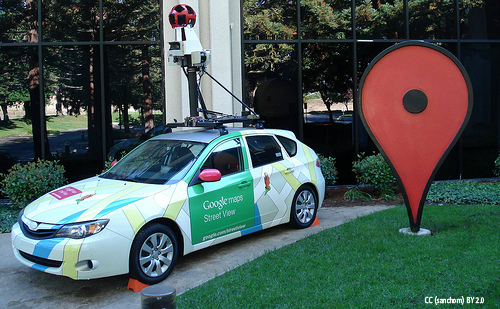

The place: corner of Córdoba and Esmeralda, City of Buenos Aires. The time: 10.15 am. Images of pedestrians, buildings, cars and city landmarks are about to become bits of information on their way to digital stardom. It’s hard not to notice a multi-colored car with a cutting-edge camera on its rooftop. It creeps quietly through streets and avenues while recording everything in its path. The future is here and it brought with it an avalanche of potential benefits and, of course, potential problems.

Street View, initially launched in the US in May 2007, found its way to Argentina in the last month and begun a tridimensional record of the City of Buenos Aires, the Greater Buenos Aires area, La Plata, Rosario, Santa Fé, and Córdoba. However, before those images could even become operational (since the technical process for uploading them takes eight months to one year according to Street View), they are already being challenged by critics in different sectors. This is largely due to the wide range of experiences in other countries, where this technology has been anchored for some time. Those who are concerned with potential privacy issues fear that past mistakes may be repeated or rights violated, which is more likely to happen in current times.

The right to intimacy –and its subsequent referral to the right to self-image– seems to be at the core of these main objections. When this multi-colored vehicle carrying a sophisticated camera on its rooftop takes our picture without our consent, a crucial issue arises as the taking of images clashes with Personal Data Protection norms in force in many countries, including Argentina. When this happens, image-gathering practices are subject to criticism and result in claims against Street View’s service altogether.

In response to similar criticism, since 2008, Google has developed an algorithm that is able to automatically shade faces and automobile license plates. But many think this isn’t enough. As with Facebook, for example, Google’s regional management has made it clear that once photos are uploaded to Street View, users who are concerned about their rights will be able to report images they feel are inappropriate and submit them for review and ultimate removal from the system.

But critics take it a bit further and question, for instance, the collection of images of fronts of people’s houses. It has been argued that under certain circumstances, the identification of a particular home may affect the privacy of the homeowner for various reasons. In such cases, the company offers the possibility –through concrete claims– of requesting removal of the images affecting said homes. Once again, these measures don’t seem to suffice for preventing individualization in every case. In fact, in different regions of Europe, this system –which was originally designed to offer services to users who wished to visit different cities and their surrounding metropolitan areas online– has been subject to less conventional uses. Tax inspectors have not hesitated to use it to their own advantage as an alternative method for facing traditional forms of evasion by comparing Google Street View images to property records in search for undeclared constructions. We face a paradox when new technologies that were developed —in essence— for private user services are ultimately used against them, or at least in detriment of their pockets.

A final concern, that although unrelated to the issue of photographs still causes concern mostly in the US and Germany, is the capturing of private information about pedestrians through the Wi-Fi system used by Google’s vehicles. Image-gathering vehicles also traced wireless internet hot spots. However, it has been reported that automatically gathered data included e-mails, messages, passwords, addresses and phone numbers of unsuspecting individuals who were connected to a Wi-Fi network using different electronic devices as the vehicles photographically mapped their area. The company has lost numerous cases before the Courts and has committed to improving its security policies to resolve this issue.

At a local level, Google has been sued in La Plata, Province of Buenos Aires, where a writ of amparo[*] has been filed to prevent the company from capturing images. The plaintiff sustained that the capturing of fronts of homes and pedestrians without consent violates the right to privacy of the subjects in the images. The First Instance Court[**] dismissed the case for deeming that the right to intimacy and privacy were not being violated since the images were obtained on public pathways. The decision has been appealed.

Meanwhile, Google’s automobile continues to roam the streets of the city. We see it over and over again. And it, in turn, also sees us.

_____________________________

[*] Translator’s Note: Under Argentinean law a writ of amparo is a remedy for the protection of constitutional rights.

[**] Translator’s Note: Similar to a First Circuit under Common Law.

Translated by Paula Arturo